The Magic of Digital Signatures on Ethereum

- What is a cryptographic signature?

- Standardisation of signed messages

- Verifying signatures with smart contracts

- Conclusion

- References & Related Articles

Cryptographic signatures are a key part of the blockchain. They are used to prove ownership of an address without exposing its private key. This is primarily used for signing transactions but can also be used to sign arbitrary messages. In this article you will find a technical explanation of how these signatures work, in the context of Ethereum.

Disclaimer: cryptography is hard. Please don’t use anything in this article as primary instruction for the implementation of your own cryptographic functions. Even though extensive research has been done, the info provided here may be inaccurate. This article is for educational purposes only.

What is a cryptographic signature?

When we talk about signatures in cryptography, we talk about some kind of proof of ownership, validity, integrity, etc. For example, they can be used for:

- Proving that you have the private key for an address (authentication);

- Making sure that a message (e.g., email) has not been tampered with;

- Verifying that the version of MyCrypto you downloaded is legitimate.

This is based on mathematical formulas. We take an input message, a private key and a (usually) random secret, and we get a number as output, which is the signature. Using another mathematical formula, this process can be reversed in such a way that the private key and random secret are unknown but can be verified. There are many algorithms for this, such as RSA and AES, but Ethereum (and Bitcoin) uses the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm, or ECDSA. Note that ECDSA is only a signature algorithm. Unlike RSA and AES, it cannot be used for encryption.

Using elliptic curve point manipulation, we can derive a value from the private key, which is not reversible. This way we can create signatures that are safe and tamperproof. The functions that derive the values are called ”trapdoor functions“:

A trapdoor function is a function that is easy to compute in one direction, yet difficult to compute in the opposite direction (finding its inverse) without special information, called the “trapdoor”.

Signing and verifying using ECDSA

ECDSA signatures consist of two numbers (integers): r and s. Ethereum also uses an additional v (recovery identifier) variable. The signature can be notated as {r, s, v}.

To create a signature you need the message to sign and the private key (da) to sign it with. The “simplified” signing process looks something like this:

- Calculate a hash (

e) from the message to sign. - Generate a secure random value for

k. - Calculate point

(x1, y1)on the elliptic curve by multiplyingkwith theGconstant of the elliptic curve. - Calculate

r = x1 mod n. Ifrequals zero, go back to step 2. - Calculate

s = k-1(e + rda) mod n. Ifsequals zero, go back to step 2.

In Ethereum, the hash is usually calculated with Keccak256("\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32" + Keccak256(message)). This ensures that the signature cannot be used for purposes outside of Ethereum.

Because we use a random value for k, the signature we get is different every time. When k is not sufficiently random, or when the value is not secret, it’s possible to calculate the private key using two different signatures (“fault attack”). However, when you sign a message in MyCrypto, the output is the same every time, so how can this be secure? These deterministic signatures use the RFC 6979 standard, which describes how you can generate a secure value for k based on the private key and message (or hash).

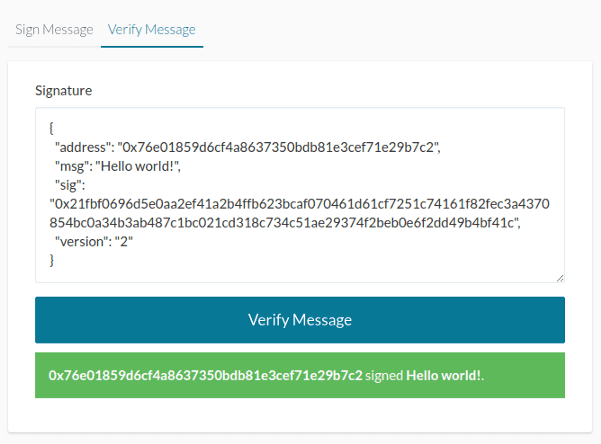

The {r, s, v} signature can be combined into one 65-byte-long sequence: 32 bytes for r, 32 bytes for s, and one byte for v. If we encode that as a hexadecimal string, we end up with a 130-character-long string, which is used by most wallets and interfaces. For example, a full signature in MyCrypto looks like this:

{

"address": "0x76e01859d6cf4a8637350bdb81e3cef71e29b7c2",

"msg": "Hello world!",

"sig": "0x21fbf0696d5e0aa2ef41a2b4ffb623bcaf070461d61cf7251c74161f82fec3a4370854bc0a34b3ab487c1bc021cd318c734c51ae29374f2beb0e6f2dd49b4bf41c",

"version": "2"

}

We can use this on the “Verify Message” page on MyCrypto, and it will tell us that 0x76e01859d6cf4a8637350bdb81e3cef71e29b7c2 signed this message.

You may be asking: Why include all the extra information, like address, msg, and version? Can’t you just verify the signature itself? Well, not really. That would be like signing a contract, then getting rid of any information in the contract, and keeping just the signature. Unlike transaction signatures (we’ll go more in-depth in those), a message signature is just that: a signature.

In order to verify a message, we need the original message, the address of the private key it was signed with, and the signature {r, s, v} itself. The version number is just an arbitrary version number used by MyCrypto. Really old versions of MyCrypto used to add the current date and time to the message, create a hash of that, and sign that using the steps as described above. This was later changed to match the behaviour of the JSON-RPC method personal_sign, so version “2” was introduced.

The (again “simplified”) process for recovering the public key looks like this:

- Calculate the hash (

e) for the message to recover. - Calculate point

R = (x1, y1)on the elliptic curve, wherex1isrforv = 27, orr + nforv = 28. - Calculate

u1 = -zr-1 mod nandu2 = sr-1 mod n. - Calculate point

Qa = (xa, ya) = u1 × G + u2 × R.

Now Qa is the point of the public key for the private key that the address was signed with. We can derive an address from this public key and check if that matches with the provided address. If it does the signature is valid.

The recovery identifier (“v”)

v is the last byte of the signature, and is either 27 (0x1b) or 28 (0x1c). This identifier is important because since we are working with elliptic curves, multiple points on the curve can be calculated from r and s alone. This would result in two different public keys (thus addresses) that can be recovered. The v simply indicates which one of these points to use.

In most implementations, the v is just 0 or 1 internally, but 27 was added as arbitrary number for signing Bitcoin messages and Ethereum adapted that as well.

Since EIP-155, we also use the chain ID to calculate the v value. This prevents replay attacks across different chains: Atransaction signed for Ethereum cannot be used for Ethereum Classic, and vice versa. Currently, this is only used for signing transaction however, and is not used for signing messages.

Signed transactions

So far we’ve mostly talked about signatures in the context of messages. Transactions are, just like messages, signed as well before sending them. For hardware wallets like Ledger and Trezor devices, this happens on the device itself. For private keys (or keystore files, mnemonic phrases), this is done directly on MyCrypto. This uses a method that is very similar to how messages are signed, but the transactions are encoded a bit differently.

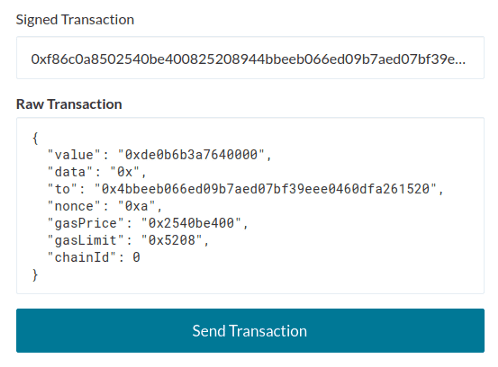

Signed transactions are RLP encoded, and consist of all transaction parameters (nonce, gas price, gas limit, to, value, data) and the signature (v, r, s). A signed transaction looks like this:

0xf86c0a8502540be400825208944bbeeb066ed09b7aed07bf39eee0460dfa261520880de0b6b3a7640000801ca0f3ae52c1ef3300f44df0bcfd1341c232ed6134672b16e35699ae3f5fe2493379a023d23d2955a239dd6f61c4e8b2678d174356ff424eac53da53e17706c43ef871If we enter this on MyCrypto’s broadcast signed transaction page, we will see all the transaction parameters:

The first group of bytes of the signed transaction contains the RLP encoded transaction parameters, and the last group of bytes contains the signature {r, s, v}. We can encode a signed transaction like this:

- Encode the transaction parameters:

RLP(nonce, gasPrice, gasLimit, to, value, data, chainId, 0, 0). - Get the Keccak256 hash of the RLP-encoded, unsigned transaction.

- Sign the hash with a private key using the ECDSA algorithm, according to the steps described above.

- Encode the signed transaction:

RLP(nonce, gasPrice, gasLimit, to, value, data, v, r, s).

By decoding the RLP-encoded transaction data, we can get the raw transaction parameters and signature again.

Note that the chain ID is encoded in the v parameter of the signature, so we don’t include the chain ID itself in the final signed transaction. We also don’t specify any “From” address, as this can be recovered from the signature itself. This is used internally on the Ethereum network in order to verify transactions.

Standardisation of signed messages

There are multiple proposals for defining a standard structure for signed messages. Currently, none of these proposals are finalised, and the personal_sign format, first implemented by Geth, is still the most common. Nonetheless, some of these proposals are very interesting.

I briefly explained how signatures are currently created:

"\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n" + length(message) + message

The message is usually hashed beforehand, so the length can be a fixed 32 bytes:

"\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32" + Keccak256(message)

The full message (including the prefix) is then hashed again, and that data is signed. This works fine for proof of ownership but may be an issue in other situations. For example, if user A signs a message and sends it to contract X, user B can copy that signed message and send it to contract Y. This is called a replay attack. EIP-191 and EIP-712 are some of the proposals that aim to solve this problem (and more).

EIP-191: Signed data standard

EIP-191 is a very simple proposal: It defines a version number and version specific data. The format looks like this:

0x19 <1 byte version> <version specific data> <data to sign>

The version-specific data depends (as the name suggests) on the version we use. Currently, EIP-191 has three versions:

0x00: Data with “intended validator.” In the case of a contract, this can be the address of the contract.0x01: Structured data, as defined in EIP-712. This will be explained further on.0x45: Regular signed messages, like the current behaviour ofpersonal_sign.

If we specify an intended validator (e.g., a contract address), the contract can re-calculate the hash with its own address. Submitting the signed message to a different instance of a contract won’t work, since it won’t be able to verify the signature.

The fixed 0x19 byte prefix was chosen, so that the signed message cannot be an RLP encoded signed transaction, since RLP encoded transactions never start with 0x19.

EIP-712: Ethereum typed structured data hashing and signing

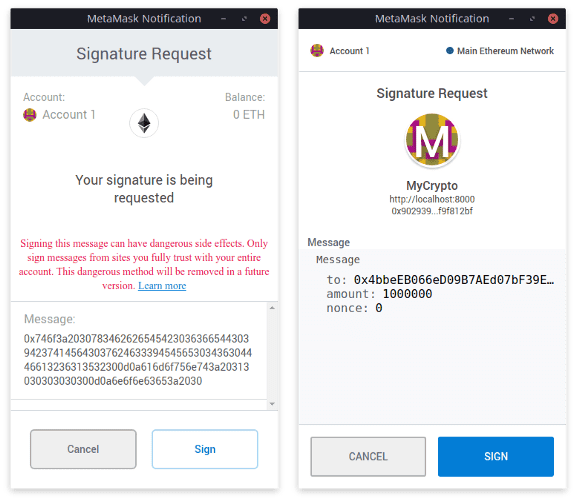

Not to be confused with ERC-721, the non-fungible token standard, EIP-712 is a proposal for “typed” signed data. This makes signing data more verifiable, by presenting it in a human-readable way.

EIP-712 defines a new method to replace personal_sign: eth_signTypedData (with the latest version being eth_signTypedData_v4). For this method, we have to specify all the properties (e.g., to, amount, and nonce) and their respective types (e.g., address, uint256, and uint256), as well as some basic information about the application, called the domain.

The domain contains information like the name of the application, the version, chain ID, the contract you’re interacting with, and a salt. The contract should verify this information, to make sure that a signature for one application cannot be used for another. This solves the problem of a potential replay attack described earlier.

The definitions for the message as seen in the image above, are as follows:

{

"types": {

"EIP712Domain": [

{ "name": "name", "type": "string" },

{ "name": "version", "type": "string" },

{ "name": "chainId", "type": "uint256" },

{ "name": "verifyingContract", "type": "address" },

{ "name": "salt", "type": "bytes32" }

],

"Transaction": [

{ "name": "to", "type": "address" },

{ "name": "amount", "type": "uint256" },

{ "name": "nonce", "type": "uint256" }

]

},

"domain": {

"name": "MyCrypto",

"version": "1.0.0",

"chainId": 1,

"verifyingContract": "0x098D8b363933D742476DDd594c4A5a5F1a62326a",

"salt": "0x76e22a8ee58573472b9d7b73c41ee29160bc2759195434c1bc1201ae4769afd7"

},

"primaryType": "Transaction",

"message": {

"to": "0x4bbeEB066eD09B7AEd07bF39EEe0460DFa261520",

"amount": 1000000,

"nonce": 0

}

}

As you can see, the message is visible on MetaMask itself, and we can confirm that what we are signing is actually what we want to do. EIP-712 implements EIP-191, so the data will start with 0x1901: 0x19 as set prefix, and 0x01 as version byte to indicate that it’s an EIP-712 signature.

With Solidity we can define a struct for the Transaction type, and write a function to hash the transaction:

struct Transaction {

address payable to;

uint256 amount;

uint256 nonce;

}

function hashTransaction(Transaction calldata transaction) public view returns (bytes32) {

return keccak256(

abi.encodePacked(

byte(0x19),

byte(0x01),

DOMAIN_SEPARATOR,

TRANSACTION_TYPE,

keccak256(

abi.encode(

transaction.to,

transaction.amount,

transaction.nonce

)

)

)

);

}

The data for the transaction above looks like this, for example:

0x1901fb502c9363785a728bf2d9a150ff634e6c6eda4a88196262e490b191d5067cceee82daae26b730caeb3f79c5c62cd998926589b40140538f456915af319370899015d824eda913cd3bfc2991811b955516332ff2ef14fe0da1b3bc4c0f424929It consists of the EIP-191 bytes, hashed domain separator, hashed Transaction type, and the Transaction input. This data is hashed again, and signed. We can then use ecrecover in order to verify the signature in a smart contract:

function verify (address signer, Transaction calldata transaction, bytes32 r, bytes32 s, uint8 v) public returns (bool) {

return signer == ecrecover(hashTransaction(transaction), v, r, s);

}

ecrecover will be explained in detail in the next section. If you’re looking for a simple library to work with EIP-712 in JavaScript or TypeScript, please have a look at this library:

For a full, detailed explanation of how to implement EIP-712 in a smart contract, I recommend this article from MetaMask. Unfortunately, the EIP-712 specification is still a draft and not many applications support it yet. Currently, Ledger and Trezor lack support for EIP-712, which may prevent wider adoption of the specification. Ledger has said they’d release an update that adds support for EIP-712 “soon,” however.

Verifying signatures with smart contracts

What makes message signatures more interesting is that we can use smart contracts to verify the ECDSA signatures. Solidity has a built-in function called ecrecover (which is actually a precompiled contract at address 0x1) that will recover the address of the private key that a message was signed with. A (very) basic contract implementation looks like this:

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity 0.7.0;

contract SignatureVerifier {

/**

* @notice Recovers the address for an ECDSA signature and message hash, note that the hash is automatically prefixed with "\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32"

* @return address The address that was used to sign the message

*/

function recoverAddress (bytes32 hash, uint8 v, bytes32 r, bytes32 s) public pure returns (address) {

bytes memory prefix = "\x19Ethereum Signed Message:\n32";

bytes32 prefixedHash = keccak256(abi.encodePacked(prefix, hash));

return ecrecover(prefixedHash, v, r, s);

}

/**

* @notice Checks if the recovered address from an ECDSA signature is equal to the address `signer` provided.

* @return valid Whether the provided address matches with the signature

*/

function isValid (address signer, bytes32 hash, uint8 v, bytes32 r, bytes32 s) external pure returns (bool) {

return recoverAddress(hash, v, r, s) == signer;

}

}

This contract does nothing more than verify signatures and would be quite useless on its own, as signature verification can of course be done without a smart contract as well.

What makes something like this useful is that a user has a trustless way to give a smart contract certain commands without sending a transaction. The user could, for example, sign a message saying, “Please send 1 Ether from my address to this address.” A smart contract can then verify who signed that message, and execute that command, using a standard like EIP-712, and/or EIP-1077. Signature verification in smart contracts can be used in applications like:

- Multisig contracts (e.g., Gnosis Safe);

- Decentralised exchanges;

- Meta transactions and gas relayers (e.g., Gas Station Network).

But what if you are already using a smart contract wallet that you want to sign a message from? We cannot simply access the private key for a contract. ERC-1271 proposes a standard that would allow smart contracts to validate the signatures of other smart contracts. The specification is very simple:

pragma solidity ^0.7.0;

contract ERC1271 {

bytes4 constant internal MAGICVALUE = 0x1626ba7e;

function isValidSignature(

bytes32 _hash,

bytes memory _signature

) public view returns (bytes4 magicValue);

}

A contract must implement the isValidSignature function, which can run arbitrary functions like the contract above. If the signature is valid for the implementing contract, the function returns MAGICVALUE. This allows any contract to verify the signature for a contract that implements ERC-1271. Internally, the contract that implements ERC-1271 can have multiple users sign a message (in the case of a multisig contract for example), and store the hash within itself. Then, it can check if the hash provided to the isValidSignature function was signed internally, and if the signature is valid for one of the owners of the contract.

Conclusion

Signatures are a key part of the blockchain and decentralisation. Not only for sending transactions, but also for interacting with decentralised exchanges, multisig contracts, and other smart contracts. There is no clear standard for signing messages yet, and further adoption of the EIP-712 specification would help the ecosystem to improve the user experience, as well as to have one standard for message signatures.

References & Related Articles

- Ethereum: A Secure Decentralised Genralised Transaction Ledger (Yellowpaper)

- EIP-155: Simple replay attack protection

- EIP-191: Signed Data Standard

- EIP-712: Ethereum typed structured data hashing and signing

- ERC-1271: Standard Signature Validation Method for Contracts

- RFC6979: Deterministic Usage of the Digital Signature Algorithm (DSA) and Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (ECDSA)